I have a faint memory of starting to watch Salaam Bombay! some years ago and not being able to watch it. The grit and raw energy was too shocking to behold. There was a feeling that I knew this film would be affective, just that I didn’t want to let it take me to that space. However, that changed today as I saw it on the big screen and it spoke to me on so many levels apart from breaking me completely with its tragedy.

Not that this is any new revelation; a lot has been written about the film and its scathing experience that transcends and becomes something more than its immediate surroundings. It is as if Mira Nair understood the spirit of the children living in Kamathipura, the spaces they occupy, the muck that makes their bed, the smells that engulf the locality and the tormented lives they lead. She put all of that into her gentle camerawork and there emerged a form that was not trying to induce pity, sympathy nor reveled in romanticism or relied on the grittiness to create shock value.

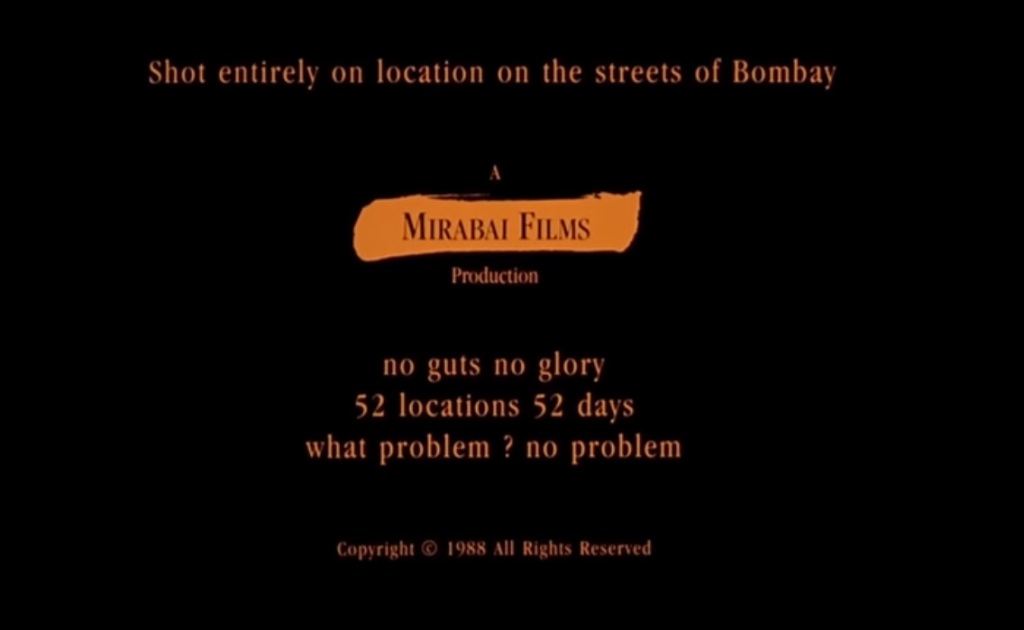

It is extraordinary how it is achieved. Her eyes, contrary to films made on ‘prostitution’ or ‘poverty’, are not vulturous; they don’t want to prey on the lives of people and add a layer of their own experience/understanding. Rather, it feels as if there are no eyes. The form almost becomes invisible, the filmmaking existing only to fulfill the means of bringing the lived reality on the forefront. This is reflected in the choices made of filming on location, working with real people living on the streets, brothel spaces and along with that, the camera not making an effort in the direction of wanting to create any sort of spectacle.

In the middle of the overwhelming tragedy present in its frames, Nair creates moments of grace and flowery innocence. Her characters are cheerful amidst the everyday turbulence. She magnifies the supposed “ratholes” of the city and takes you closer to the stench, making you realize some glimpses of beauty along the way, which otherwise would have never caught your shadowed eyes. It is the Bombay everyone whispers about in muted conversations but no one wants to take a look at. Her aesthetics are aptly described by the pimp, Baba, played by Nana Patekar, who calls another character ‘a gulaab in the gutter’. The film and its style seem to be essentially derived from this understanding.

Apart from being an important and powerful document, Salaam Bombay! is also a textbook on making a film on complicated subjects that are not part of the maker’s lived reality. It stands in direct contrast to the glittery aesthetics of Bhansali and others who have made films made in the same world, although with a purely different eye. It tells you that, at its most rudimentary level, filmmaking is about becoming one with the subject. If it is talking about unjust power structures present around, it should not end up becoming yet another pillar of the same world that it aims to critique. The indulgence in aesthetics should not come at the expense of overpowering everything else, including the subject matter. Rather, it is about simplifying the complexities and breaking it down to the bare minimum. It should lay allegiance only to the seed in order to really bloom into the tree later.